Written by Nancer Ballard; ed. assistance by Savannah Jackson.

I believe that the Seeker’s Journey may begin, or we may veer toward a new heading, when we bump up against the limits of our imaginations. I’ve always been told (and have believed) that I have been blessed and cursed with a “good imagination.” Over the years, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to prove I could actualize what my mind imagines is possible in the face of those who have wanted me to quit, “to be more realistic” or reduce my goals unless a successful outcome is relatively certain. And I have not always been a big fan of failure.

And yet…. In every creative project, I hit the wall.

That place where nothing is working, or rather, I am struggling with something that isn’t working the way I want it to, or it doesn’t feel quite right, but I don’t know what to do to make it feel right. I’ve spent a lot of time believing that I wasn’t good enough, or that I wasn’t trying hard enough, or that I am stupid, or there is something else wrong with me. And, if I can just figure out what is wrong with me and fix it, then my work, my journey, and my life will proceed smoothly. But I can never fix what I assume, in these moments, must be wrong with me, so, eventually, I turn back to the problem at hand and muddle along.

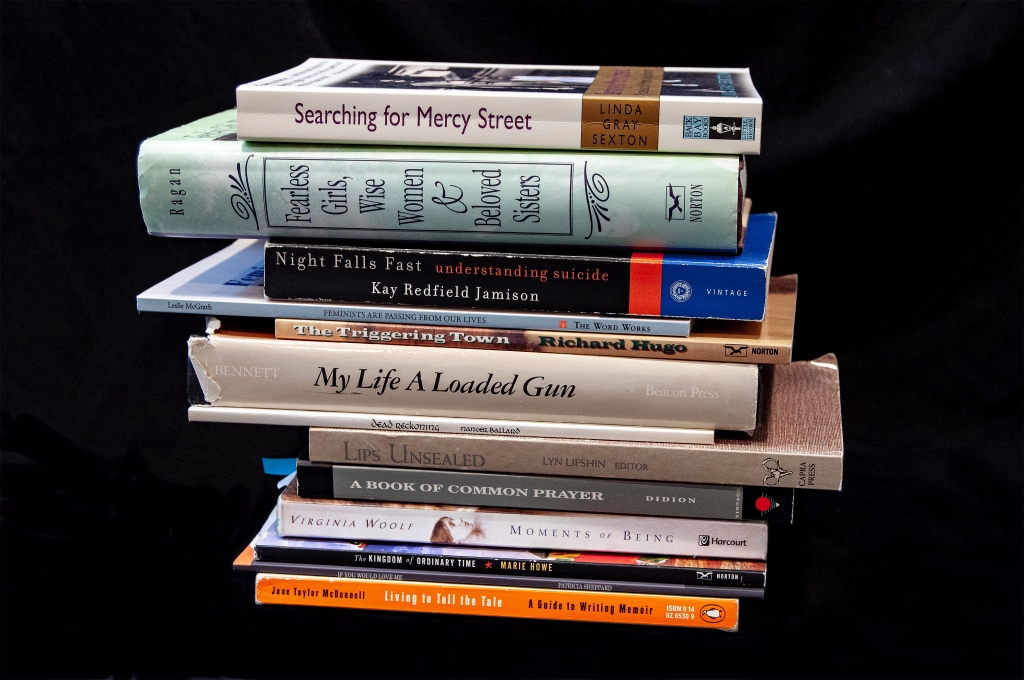

Although we commonly assume that our senses’ and mind’s job is to enable us to accurately perceive reality, psychologist Dennis Proffit of the University of Virginia, and cognitive scientist, Donald Hoffman of the University of California Irvine, remind us that what we see, hear, and feel is largely determined by our automatic, pre-conscious, moment-to-moment assessments of the actions that our surroundings are prompting us to take. When we are looking for a book, we focus on the titles and don’t notice the color of the carpet or the paint condition of the shelf unless they are somehow related to finding the desired book.

Once the book has been found, or the hunt abandoned, we then go on to perceive and focus and store in memory other things related to what we plan to do next, or the things that are integral to the reason we sought the book.

The reality is, there are always more problems and sub-problems than we have the answers for. As Shakespeare’s Hamlet put it, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” We hit the limits of our imagination, not because we are stupid, or ignorant, or naïve, but because that’s how our brains are built. We couldn’t function if everything we perceive, remember, or intuit about the environment, ourselves, and those with whom we are interacting had to be held in working memory or accessible consciousness. Our brains aren’t able to handle that much interacting information, nor did we evolve to do so.

Similarly, when we day dream or think about our life, or career, or a relationship, or a project, we can’t know all the details, nor process all that will be required in the future as we proceed on our journey (or journeys). We also can’t account for everything that could possibly affect us, our environment, our journey, the ones we love, and the world. They are all interconnected, so the solution is not to decide that we are only going to focus on the world instead of those close to us, or that we will focus only on ourselves instead of the world. Thus, no matter how smart, or creative, or driven, or limited we are, if we are present to the world and ourselves, we will hit the end of the known world. That blankness or darkness, which feels so uncomfortable (or worse), is the prompt that tells us to continue seeking.

The Seeker’s Journey may be the most profound journey (but not the only, or most pleasant journey in all moments) that we can take. The word profound comes from the Latin “pro” meaning forth and “fundus” meaning bottom, or coming from the very bottom. The Seeker’s Journey is our most profound journey because it is a physiological imperative that we face (or avoid). The seeking impulse is part of our nature, without regard to cultural constraints or institutional, religious, or political oppression, although these can be a major concern of a Seeker’s Journey. Our brains and bodies are magnificent and limited, and we are constantly asking our senses and minds to simultaneously focus on the subjects of our concern, our relationships, the world, and ourselves, and all of these are constantly and interactively changing.

To be a seeker is to meet the unknown at the edge our known reality, and to do this consciously and willingly without disrespect for what we already are and have done. The Seeker’s Journey often calls upon us to change course, not because we were misguided before, but because what was suitable previously may not fit with what we understand ourselves and our world to be now. The reward for changing course, or wholeheartedly making the journey, may not be material success, or external approval, or permanent anything– the Seeker’s reward is the felt miracle of being alive.

In an upcoming blog, we will explore the role and mechanism of transformation in The Seeker’s Journey.