Written by Nancer Ballard; ed. assistance by Savannah Jackson.

Now that over one third of the world has been ordered to stay at home unless they are working in essential services, people are watching a lot of movies. So, we thought this would be a good time to update the Heroine’s Journey Project Drama and Film page and to offer our thoughts on three recent Academy Award winning films, Moonlight, The Shape of Water, and Parasite, that challenge conventional journey arcs.

The 2016 Best Picture winner is a three-part coming-of-age drama about Chiron, an African American boy in Miami, Florida who wrestles with bullying over his sexuality and with a pervasive drug culture neighborhood.

In Part 1, a Cuban drug dealer finds Chiron, who has been dubbed “Little,” hiding from a group of bullies in a crack house. The drug dealer, Juan, takes Chiron to his own house where he and Juan’s girlfriend, Teresa, make up a spare bed for Chiron. When Juan returns Chiron to his mother the next morning, Chiron’s mother, Paula, punishes the boy for worrying her although she is an addict and often out later herself. Juan and Chiron continue to spend time with each other and Juan teaches Chiron how to swim. When Juan sees Paula smoking crack with one of his customers, he berates her for being addicted and neglecting her son. Paula lashes back at Juan for having sold her crack in the first place. She suggests she knows why Chiron is bullied by his peers, saying he walks like a girl. The next day Chiron tells Juan and Teresa that he hates his mother and asks what “faggot” means. In a surprising departure from machismo, Juan describes it as “a word used to make gay people feel bad.” He tell Chiron that it’s okay to be gay and that he shouldn’t let others bother him. Chiron asks Juan whether he’s really a drug dealer and leaves when Juan answers truthfully. In short, in Part I, the film evokes and shatters masculine stereotypes, mixing objectification (Juan vis a vis his customers) with sympathy (for Chiron), indifference (Juan’s attitude as a crack dealer) with tenderness (for Chiron and Teresa), denial and bravado (in drug dealing scenes) with perspective and sociological imagination (Juan on the beach with Chiron).

In Part II of the film, the plot seesaws between increasing cruelty and powerless good intentions. Juan has died and the teen-aged Chiron spends his time trying to escape bullying at school and with Juan’s nurturing former girlfriend, Teresa. Chiron’s mother’s crack addiction progresses and she more openly abuses Chiron, begging and threatening him for money for a fix. A classmate, Kevin, is Chiron’s only friend. One night Kevin sees Chiron at the beach, and they smoke a joint let down their defenses, talk, and then kiss. Kevin masturbates a shy Chiron. The next day the leader of the school bullies threatens Chiron, and Kevin is manipulated into punching Chiron, believing that this will save Chiron from a worse fate. When Chiron refuses to surrender to Kevin’s punching the gang beats up Kevin. The next day an enraged Chiron smashes a chair over the bully’s head. The police arrive, and Chiron is sent to a juvenile hall. Rather than meeting and succeeding at increasing difficult obstacles as would happen in a hero’s journey, Chiron is caught in downward spiral in which neither he, nor sympathetic others, can protect him.

In Part III, machismo faces off against emotional connection and reality. Chiron, now a much larger, muscular adult, goes by the nickname of “Black.” After being released from prison, he becomes a drug dealer in Atlanta. His mother, much the worse for wear, now lives in a treatment center. One day he receives a call from his old friend Kevin who invites him to visit if Chiron is ever in Miami. Chiron visits his mother and tells her he is dealing drugs. His mother expresses regret and apologizes for not loving him when he needed it most and tells him she loves him even if he does not love her back. Later Chiron drives to Miami to visit Kevin, who now works as a cook at a diner. Kevin tells him he has a child by an ex-girlfriend and although the relationship is over, he enjoys acting as a father. When Kevin asks him about his life, Chiron is silent. Chiron asks Kevin why he called and Kevin plays a song on the juke box that he says reminds him of Chiron. After Kevin serves him dinner, they return to Kevin’s apartment. Kevin tells Chiron he is happy although his life didn’t turn out as he had thought. Chiron then breaks down and admits that he hasn’t been intimate with anybody since their encounter years earlier. Kevin comforts him and they embrace. Although the could suggest a happy ending, the film rejects the easy ending. Instead, the film closes with a flashback of young Chrion standing, alone, on a beach looking at the ocean where Juan taught him to swim, and where, later, he and Kevin would kiss. The beach may signify that it is still possible for Chiron to choose again, to envision a different future, but he is standing alone. There’s no suggestion that such change would be glamorous, quick, or easy.

Shape of Water, the 2017 Best Picture winner, is a dark fantasy about a mute young female cleaner, Elisa Esposito, who works at a high security government laboratory where she falls in love with a humanoid-like amphibian creature.

Elisa, who was found abandoned by the side of a river with wounds on her neck as a child, communicates through sign language. In the laboratory she begins to visit the Amphibian Man and non-verbally communicates with him. When she learns that his keepers (an American researcher and a Soviet spy posing as a researcher) plan to harm the Amphibian Man, she persuades her next door neighbor to help her save the creature. They plan to release him back into the ocean, but Elisa must bring him to her apartment until it rains and the canal that leads to the ocean is open. Various complications and a somewhat bizarre sex scene (unless one views the film as metaphor) ensue, and viewers discover that the Amphibian Man has magical healing powers. The laboratory researchers discover the Amphibian man is missing and chase Elisa and her neighbor to the canal where they are about to release the Amphibian Man. The lab researchers shoot the Amphibian Man and Elisa, but he is able to heal himself in time to slash the shooter’s throat and jump into the canal with Elisa. Underwater, the scars on Elisa’s neck open to gills, and Elisa and the Amphibian Man embrace.

In the voice-over narration, the next door neighbor states that he believes Elisa and the Amphibian Man lived “happily ever after in love.” Because the neighbor can’t really know what happens after Elisa and the creature sink into the ocean, the story can be interpreted as a hero’s journey in which two misfits find themselves and have a “happily-ever-after” conclusion, or as Elisa dying while trying to save a “creature” that will never be accepted in the world, or as Elisa and the creature attempting to flee (successfully or unsuccessfully) a world into which they will never fit. As a fairy tale, The Shape of Water follows the conventional hero’s journey arc. To the extent that one views the film as metaphor, the story can also be interpreted as a heroine’s journey metaphor in which Elisa is pursuing wholeness whether one interprets the Amphibian Man as an aspect of Elisa (and following Maureen Murdock’s heroine’s journey arc) or as a separate outcast who supports rebirth of Elisa’s true full creature self (Victoria’s Schmidt’s heroine’s journey arc).

Parasite, the 2019 winner and first non-English language film to win Best Picture, is a dark “thriller” directed by Bong Joon-ho (who also co-wrote the screenplay with Han Jin-won). The movie follows the lives of a poor South Korean family of four, the Kim Family, who live in a small basement apartment and are trying to survive on low-paying temporary jobs. A friend of the twentyish- year-old son, Ki-woo, suggests that Ki-woo take over his job as an English tutor for the daughter of the rich Park family. Once he is hired as tutor, Ki-woo sees additional opportunities that could come from working for the Parks. He helps his sister, Ki-jeong, pose as an art therapist to secure a job as counselor for the Parks’ hyper-active son. Ki-jeong then gets the Parks’ chauffeur fired, and the Kims’ father takes over as the new chauffeur. They then get Parks’ housekeeper’ fired, and the mother becomes the new housekeeper. Although the Kims’ rise in fortune looks something like a Hero’s journey and they sporadically see themselves in that light, the father continually disavows any plan or vision of sustained success.

Sure enough, when the Parks go on a camping trip and the Kim family assembles in the Park’s home to revel in the luxuries of the mansion, the former housekeeper returns and reveals that her husband has been living in a secret bunker below the house built by the prior owner. The original housekeeper and her husband’s deception are eerily similar to the the Kims’ who keep their own family basement living arrangements a secret from the Parks. After bad weather disrupts the camping trip, the Parks return home early and a melee breaks out in the Parks’ house. After several more plot turns in which a member of the Parks family, the Kim family, and the original staff’s family are killed, the movie ends in the Kims’ basement apartment where the son, Ki-woo, is writing a letter to his father, vowing to earn enough money to purchase the Park’s house, set him free, and reunite the family. Although the actor who played Ki-woo has suggested in interviews that he believes this could happen,

Parasite’s director has stated that he believes Ki-woo’s dream is only a fantasy and that the story’s characters end up where they started. Each family is “parasitically” dependent on the other as they focus on getting ahead; each family loses some of its members but gets nowhere. There is no economic/class journey arc because both families end up where they started (minus a member) and no one seems the wiser for having lived their story. The beauty of Parasite, is that it takes our natural (or at least conventional) inclination to expect that the story will become a Hero’s Journey (underdog wins) or a cathartic Tragedy (greedy characters get what they deserve) and teases and then frustrates our expectations while provoking us to reckon with class inelasticity both literally and metaphorically.

Although the majority of the winning films follow the Hero’s Journey pattern, there has been a significant increase in Heroine Journey films in recent years. More recently, film makers have also gravitated toward making movies that involve ambiguous journeys (The Shape of Water) or resist concluding a journey arc (Moonlight and Parasite). We believe this trend is based on an increasing recognition of the complexity of an interconnected global world and the legitimacy of multiple perspectives. We’d love to hear from our blog readers on what films you have been watching that follow a Heroine’s Journey, include multiple journeys, or provide variations on a journey arc as a meta-statement on the content of the movie.

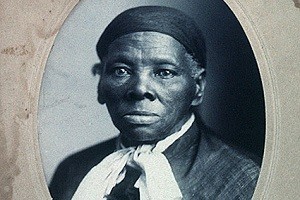

Unable to bear a lifetime of enslavement, she flees north on foot (leaving her husband behind because she does not want to endanger his free status) and makes it to Philadelphia, a “free” state. Tubman joins the Underground Railroad and repeatedly risks her life to bring hundreds of black slaves to freedom even after her former owner places a large bounty on her head. Her ability to guide so many runaway slaves to freedom earns her the nickname, “Moses.” How does an actual person, rather than a mythical god or cartoon character pull this off?

Unable to bear a lifetime of enslavement, she flees north on foot (leaving her husband behind because she does not want to endanger his free status) and makes it to Philadelphia, a “free” state. Tubman joins the Underground Railroad and repeatedly risks her life to bring hundreds of black slaves to freedom even after her former owner places a large bounty on her head. Her ability to guide so many runaway slaves to freedom earns her the nickname, “Moses.” How does an actual person, rather than a mythical god or cartoon character pull this off?

Although the movie follows a Hero’s Journey narrative arc, I suspect that Tubman’s lived experience was at least as much a

Although the movie follows a Hero’s Journey narrative arc, I suspect that Tubman’s lived experience was at least as much a  Tubman was periodically recognized for her contributions to the Underground Railroad and the Civil War as a spy, nurse, scout, strategic advisor, and troop leader. However, she never received any pay for her work in the war and was denied veteran’s compensation for many years. After being heralded by newspapers for her work in the war, she was accosted by a train conductor while riding back to New York, where her parents lived, and was instructed to move to the less desirable smoking car. She produced government papers entitling her to ride in the car she was in and refused to move, whereupon the conductor enlisted several other passengers to help him force her to move, breaking her arm in the process. Most of her life, Tubman was penniless or nearly so, and what money she had was often spent providing food to the boarders who had even less than she did.

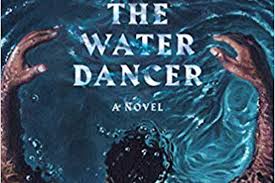

Tubman was periodically recognized for her contributions to the Underground Railroad and the Civil War as a spy, nurse, scout, strategic advisor, and troop leader. However, she never received any pay for her work in the war and was denied veteran’s compensation for many years. After being heralded by newspapers for her work in the war, she was accosted by a train conductor while riding back to New York, where her parents lived, and was instructed to move to the less desirable smoking car. She produced government papers entitling her to ride in the car she was in and refused to move, whereupon the conductor enlisted several other passengers to help him force her to move, breaking her arm in the process. Most of her life, Tubman was penniless or nearly so, and what money she had was often spent providing food to the boarders who had even less than she did. protagonist Hiram Walker is portrayed as a male soul-kin to Harriet Tubman. Both were born slaves and both have similar talents for feats of miraculous transportation. In the magical realism of the novel, this talent is referred to as “conduction”—the ability to move people “magically” from one place to another based on the strength of the conductor’s desire and memory. Coates portrays Tubman as a mythical figure who appears and disappears and reappears at important moments. Hiram Walker, her psychic kin, is much more humanized and his story allows Coates to explore the psychological implications of post-freedom identity and purpose. Walker, too, becomes a daring agent for the Underground Railroad and much of the book leans toward a hero’s journey until he must confront how to integrate his family and community ties into his quest to fight slavery and re-connect families separated by it. I believe The Water Dancer is ultimately more of a heroine’s journey than a hero’s journey.

protagonist Hiram Walker is portrayed as a male soul-kin to Harriet Tubman. Both were born slaves and both have similar talents for feats of miraculous transportation. In the magical realism of the novel, this talent is referred to as “conduction”—the ability to move people “magically” from one place to another based on the strength of the conductor’s desire and memory. Coates portrays Tubman as a mythical figure who appears and disappears and reappears at important moments. Hiram Walker, her psychic kin, is much more humanized and his story allows Coates to explore the psychological implications of post-freedom identity and purpose. Walker, too, becomes a daring agent for the Underground Railroad and much of the book leans toward a hero’s journey until he must confront how to integrate his family and community ties into his quest to fight slavery and re-connect families separated by it. I believe The Water Dancer is ultimately more of a heroine’s journey than a hero’s journey.

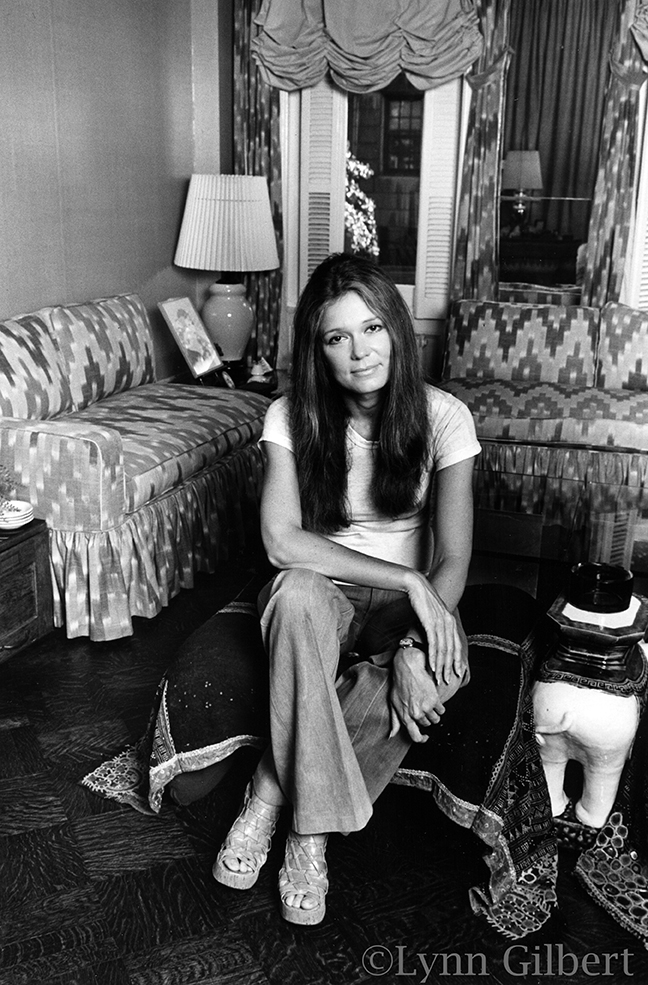

Gloria had her own #MeToo moment before the movement was named. A New York Times editor suggested to Steinem that they “discuss her work in a hotel room this afternoon”; and in 1963, when she was sitting in a cab ride in between Gay Talese and Saul Bellow, Talese said, “You know how every year there’s a pretty girl who comes to New York and pretends to be a writer? Well, Gloria is this year’s pretty girl.”

Gloria had her own #MeToo moment before the movement was named. A New York Times editor suggested to Steinem that they “discuss her work in a hotel room this afternoon”; and in 1963, when she was sitting in a cab ride in between Gay Talese and Saul Bellow, Talese said, “You know how every year there’s a pretty girl who comes to New York and pretends to be a writer? Well, Gloria is this year’s pretty girl.”

Her story is not defined by an external quest like the

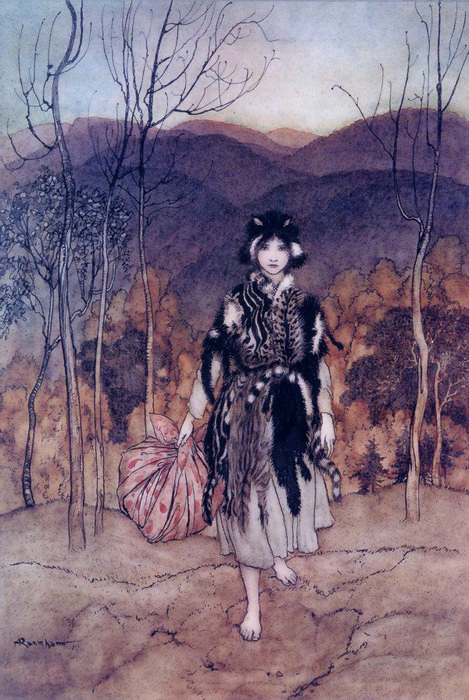

Her story is not defined by an external quest like the  In many recent stories the wild place is the big city, the center of sin and crime. The heroine has been taught all her life to fear this place, yet she is drawn to it.

In many recent stories the wild place is the big city, the center of sin and crime. The heroine has been taught all her life to fear this place, yet she is drawn to it.

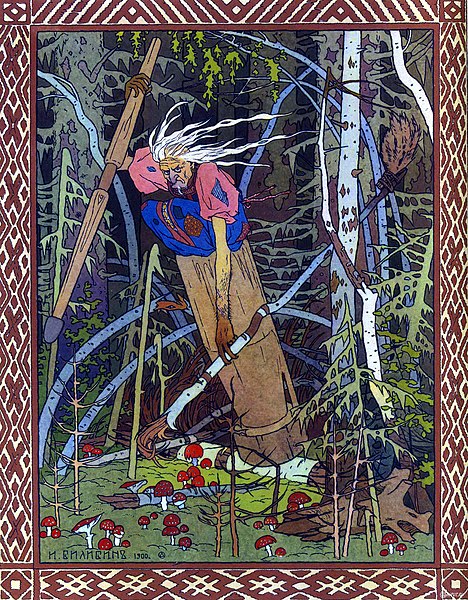

he role of women in all facets of life is a topic I return to again and again. I am especially attracted to women from more rural, indigenous cultures.

he role of women in all facets of life is a topic I return to again and again. I am especially attracted to women from more rural, indigenous cultures. What about the Lowell Mill workers? Women throughout the world have played important roles in virtually every form of constructive peaceable work from antiquity to the present. The piece’s subtitle, Women in Labor, is a play on the concept of women forever giving birth creatively to the world on many levels.

What about the Lowell Mill workers? Women throughout the world have played important roles in virtually every form of constructive peaceable work from antiquity to the present. The piece’s subtitle, Women in Labor, is a play on the concept of women forever giving birth creatively to the world on many levels.