Written by Savannah Jackson; ed. assistance by Nancer Ballard.

How do our journeys interact with others’ journeys and larger world forces? In this post we examine the role of social context and social awareness in a protagonist’s consciousness, decision-making, and journey—a topic that is particularly relevant to these times of a pandemic, a time in which we are acutely aware of how we affect and are affected by others, and a time when we are watching to see how other communities across the globe are handling situations which may be on our doorstep tomorrow.

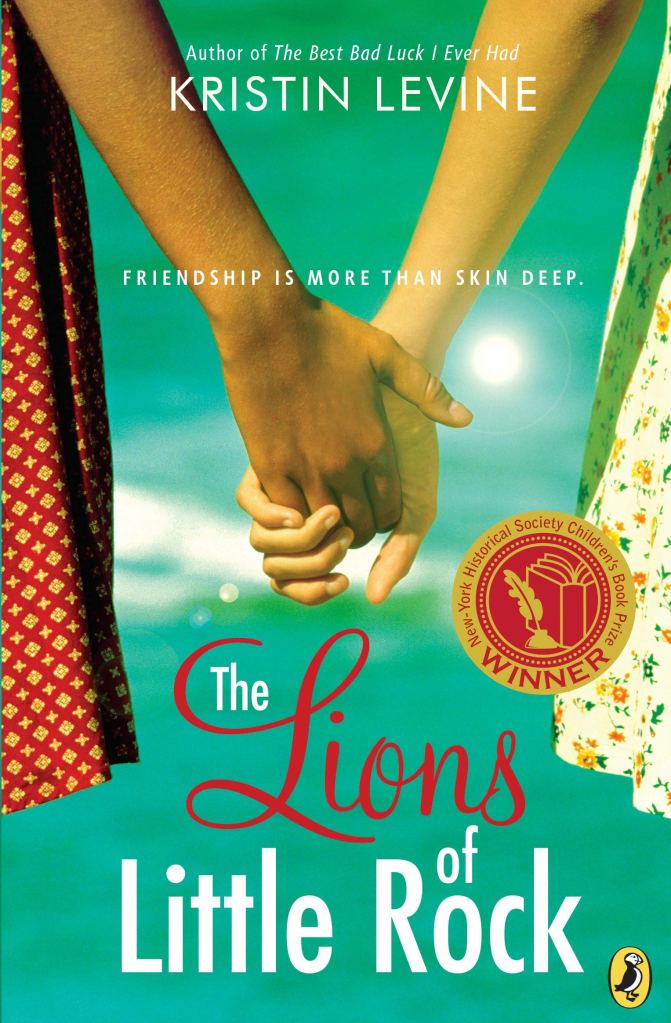

In the middle-grade novel, “The Lions of Little Rock,” Kristin Levine tells the story of racial school segregation in Arkansas in the late 1950s. Twelve-year-old Marlee is quiet and shy before she meets Liz, who helps Marlee become more confident as their friendship grows. When Liz disappears from school without warning, Marlee learns that Liz was removed from the all-White school because she was actually a Black girl “passing” as White. Marlee begins to talk to people and learn more about the social context she is growing up in. Her own parents don’t agree on racial segregation, and as these tensions grow within her own home, Marlee also sees them grow within the community. Marlee comes to understand how her relationship with Liz and Liz’s experiences are not unique. She realizes that their experiences are not fully within their control—and not only because they are children. Marlee joins integration efforts, but is unable to prevent a bombing attack on the home of a Black family. She is ignored by the police, but ultimately supported by her family. She fights to defend her relationship with Liz, but ultimately cannot stop them from being torn apart when Liz’s family moves away. She better understands her privileges and her friend’s hardships. She repeatedly takes action and discovers new communities but she also sees how her actions are not able to bring about the societal changes she wants—no matter how determined and passionate she is. By the end of the book, Marlee has developed a social awareness and has a deeper understanding of the interplay between her individual actions and experiences, and the larger forces beyond her control in the world.

“The Lions of Little Rock” illustrates how unrealistic it is to force complex real-world situations into the Hero’s Journey myth structure. It is unrealistic because in the real world, individual actions are embedded within a larger environment that is not susceptible to quick change for the better. The Hero’s Journey emphasizes the supreme power of individual agency (or of a group acting as one) rather than the complexity of interconnected personal and collective struggles. In many—if not most—hero’s journey stories, the hero solves their own problems through personal effort and brings about decisive changes to their world or community. The hero does not see how they are deeply embedded within a social context but see themselves as outside of and above it. For example, in Wonder Woman, in the course of completing her own journey, Diana also ends World War II and secures victory for the Allies. But such decisive, sweeping changes are rarely, if ever, possible in the real world.

In the late 1950s, the same time period described in “The Lions of Little Rock,” American sociologist C. Wright Mills articulated what he called the “sociological imagination.” Mills believed that people would feel less helpless and more empowered if they could recognize the societal and structural causes that shape their individual personal experiences. Mills suggested that people often feel stuck in their daily lives because they do not recognize how their personal troubles connect to and are part of larger public issues.

For instance, one person may feel like their fear of getting sick is a personal trouble because they know they cannot afford treatment and because if they miss work, they will not be able to buy food for their family. However, when a significant percentage of the population worries that they cannot afford to miss work or pay for treatment, each experience is part of a larger public issue. Moreover, each person who cannot afford treatment and continues to work while sick may inadvertently infect others. Thus, one person’s health options and decisions impact and are impacted by larger economic and societal factors that are beyond their individual merit, fault, or control.

The sociological imagination is most often discussed in the context of people who are at the bottom of social structures, but it can shed light on the experiences of those in advantaged positions as well. In the simple but powerful article, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, author Peggy McIntosh lists forty-seven ways in which White people benefit from their privilege as members of a dominant group in society. McIntosh identifies experiences such as: “If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race,” and “I can swear, or dress in second hand clothes, or not answer letters, without having people attribute these choices to the bad morals, the poverty or the illiteracy of my race.” Such advantages are often considered to be “the norm,” which make them invisible to the people who benefit from them. By drawing explicit attention to everyday White privileges, McIntosh encourages members of dominant groups to examine their role in a racially (or otherwise) divided society.

As Mills points out, recognizing privileges and disadvantages can enable us to see what seem like personal shortcomings in a larger context so that collective responses can be developed to alter circumstances through structural change. When this is not possible within the desired time frame, seeing your own experience, and others’ experiences, in a larger context, promotes empathy towards others and towards yourself. Such empathy enables meaningful changes to take place at a local level and may also bring about imperceptible but cumulative changes in the larger world.

The sociological imagination usually plays a key role in a Heroine’s Journey story. The heroine works to integrate their understanding of themselves (including their values and social position) with a world that is not of their making. The very idea of wrestling with “the feminine” and “the masculine” requires one to examine the intersection between one’s own life experience and the roles and expectations ingrained in the larger culture. In order to heal, the heroine must come to understand how masculinity/masculine values and femininity/feminine values are defined by the culture, and what role those attributes play in the heroine’s own self-definition.

The sociological imagination also frequently plays an important role in a Journey of Integrity. In this journey, the individual frequently must make a decision that involves weighing personal interests against his or her ethical values on taking action to benefit the larger world. See our post on Marie Jovanovich’s decision to testify before Congress during the U.S. Impeachment hearings. The weighing process requires the protagonist to consider how their personal experiences and actions relate to and are part of larger realities.

The sociological imagination can also be a part of a Healing Journey. For example, a story about opioid addiction could address the role doctors and pharmaceutical companies play in making opioids seem less addictive than they are, or in making them the first rather than last response to chronic pain. This recognition may be important to the healing person to prevent him or her from feeling that their addiction is just a personal weakness, or to help them to work through their denial, shame, or prejudices for being someone “like that.” Of course, someone struggling to overcome an opioid addition could also formulate their story without significant attention to the larger societal structures that play a role in access to opioids and treatment availability.

The Coronavirus pandemic is shining a spotlight on the ways in which our individual and systemic vulnerabilities and our responses affect individuals, organizations, governments, countries, and the world. Some journey stories do not include any attention to the role of social context. However, a sustained sense of Wholeness is not possible without attention to context because context is part of the Whole, and each part affects the other parts and the Whole. Context is not static, nor is wholeness. As our context changes around us, and as we ourselves change, so too must our understanding of wholeness grow.