Written by Nancer Ballard; ed. assistance by Savannah Jackson.

One of the questions we are most frequently asked by our readers and workshop participants is “How do you know where a story ends?”

Where to end a story is one of the most important decisions a storyteller makes. A story ends when a central character finds what they are looking for—even if it wasn’t what they thought they set out to find—or finds what they didn’t know they were looking for.

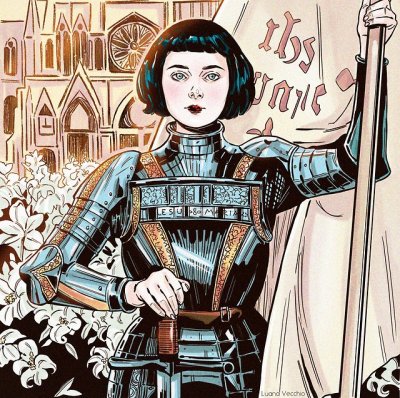

Where and how a teller ends (and begins) a story frequently determines whether the story is a hero’s journey, heroine’s journey, or other journey story. The ending can be even more important than the nature of the events being described. For example, if you tell the story of Joan of Arc and end with her leading the French to an unlikely victory over the English at Orleans, the story would likely be a hero’s journey. If the story then continues through her capture and trial for witchcraft—depending on the perspective—it could be a hero’s journey (Joan as martyr) or a heroine’s journey (Joan seeking understanding and serenity in the face of a rigged trial). If the storyteller then reflects on Joan’s life and meaning from the present day, the story could be a hero’s journey characterizing Joan as an inspiring icon to generations of women and the French following her death. It could also be a heroine’s journey that reflects on recent theories regarding Joan’s mental health, or on the differences in how passionate male and female leaders are treated. Or it could be a Journey of Integrity, in which the narrator reflects on Joan’s decision-making process through the lens of victory, defeat, and the years since her death.

The Hero’s Journey ends when the hero finds success or the ultimate boon. He has achieved his goal, returns to his society, and/or is recognized by his peers as having achieved success. The hero is a master of two worlds—the inner world which makes him a good leader/hero and the outer world which allows him to be a leader or proclaims him a hero.

The hero’s journey also ends with the implication that the hero’s success won’t be snatched away any time soon. It’s a kind of happily-ever after ending. If a sequel is anticipated, perhaps the hero’s success will lead to other complications that provide the chance for a new hero’s journey, but the success won’t be undone—at least not for that hero. If the success is undone, the former hero tends to become a supporting character (no longer the main character). They may become a wise elder or a mentor who urges the hero of the next generation to reclaim, recapture, or make additional progress on a larger problem that wasn’t anticipated when the first success was achieved.

In a hero’s journey, there is always the sense that success is right around the corner. Their journey is not envisioned as a long, imperfect struggle that will continue forever. The hero’s agency—his or her ability to bring about change—is central to the hero’s journey arc, so the journey usually ends shortly after the hero accomplishes their final feat and/or their victory/ability is hailed by others.

In a heroine’s journey, the story ends when the heroine recognizes and experiences wholeness. Life includes both success and failure, vulnerability and ability, self and others, and a larger world. The heroine’s self is not necessarily dominant or foregrounded, even over long periods of time. The heroine’s final goal is not to defeat or dismiss vulnerability, or failure, or sadness, or pain, or self, or others. Their goal is to integrate and value all these as necessary and valuable aspects of the human experience. It is rare that this experience of wholeness is solely an internal realization; a non-dual world is also manifested in the events of the story. It may be tempting to try to view wholeness as a resolution to a story in which the unpleasant aspects of life are part of the past but not the present, or new understanding will eliminate future suffering—but that is a hero’s journey.

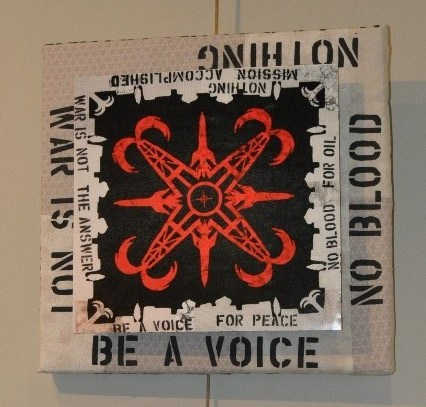

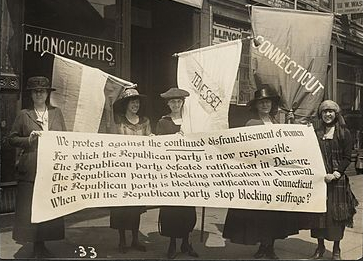

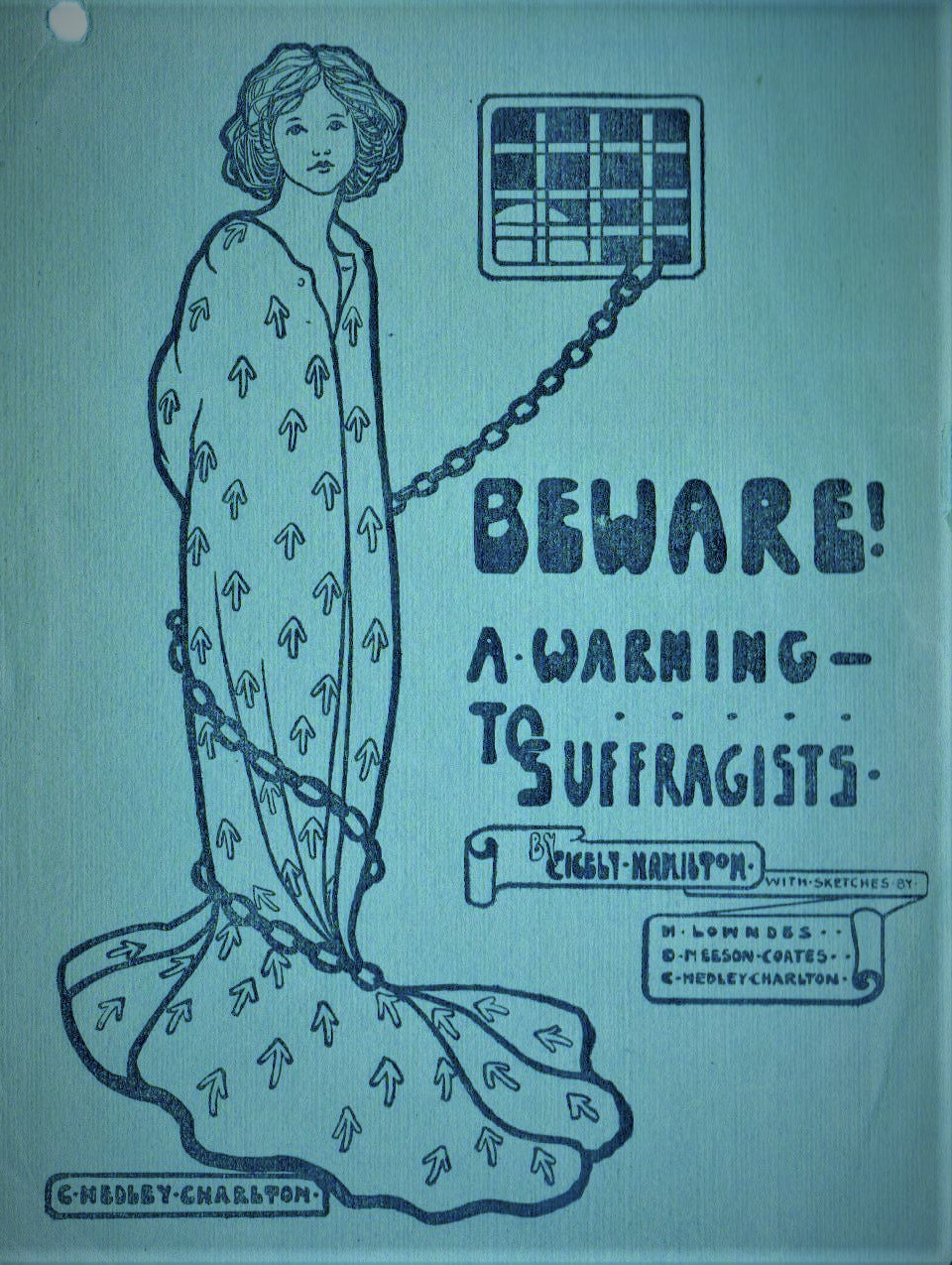

Several of our readers have wondered if the heroine’s journey is more depressing than a hero’s journey. Many heroine journey stories have heartwarming or uplifting endings. For example, in the play about the women’s suffrage movement, I Want to Go to Jail, the story ends with a celebratory moment after a group political action. However, the main characters and the audience (which has the benefit of hindsight) understand that more action will be required before women are able to vote.

Another example of a heroine’s journey that ends on a positive note is the 2018 movie, The Green Book, which tells the story of an African American pianist traveling through the American south in the early 1960’s with an Italian-American bouncer who serves as his bodyguard. The story has a heartwarming ending when the jazz pianist drives through the night so that the bodyguard can get home for Christmas. The jazz pianist is then is welcomed into their home, but it remains clear that the pervasive racism that has followed the pianist throughout his tour has been neither “solved” nor “conquered.” The odd-couple main characters have grown personally and relationally within the racist societal backdrop. The heroine’s journey doesn’t end with a sense of a “once-and-for-all” victory.

The end of the Healing Journey revolves around forgiving the self and sometimes others for not being able to control even one thing that you feel you most need to control. In this journey, the protagonist’s rage against the wound is at the center of the story. This may also appear as the apparent unfairness of an injury/illness, or the protagonist feeling overwhelmed by the cards they have been dealt. The protagonist often tries at first to solve their dilemma with a hero’s journey approach. For example, she might imagine that if she fights her illness hard enough, she will be healed, or that if she just accepts her illness instead, the conflict within will be resolved and she will get better. The hero’s journey promises that you can get well. The heroine’s journey involves finding compassion for one’s self and others whether or not you recover. The Healing Journey usually involves a point of absolute break-down, where the injured one wants to quit, and possibly die. Then there is a moment or experience of beauty that surprises them, and allows for a shift in perspective, a shaft of light to enter their consciousness. Sometimes they give up trying to control, sometimes they give up magical thinking, sometimes they give up, giving up—the action can vary. What is important is that the protagonist forgives him/herself and an imperfect world.

A Journey of Integrity involves both the protagonist action and awareness (culminating in the moment of integrity), and also the witness/viewers’ awareness of and reflection on the meaning of the protagonist’s action. These stories may end with the protagonist returning to ordinary action in the ordinary world, but they also often jump forward in time or expand geographically so that the narrator or audience can see and comment upon the protagonist’s action within a larger context.

Readers and listeners always evaluate the meaning of a story through the lens of its ending. No story has a single, objective endpoint. As storytellers, we shape the readers’ experiences and the meaning of a story through the endings that we choose.

In our next post we will discuss how the storyteller’s choice in where to begin a story affects the journey.

he role of women in all facets of life is a topic I return to again and again. I am especially attracted to women from more rural, indigenous cultures.

he role of women in all facets of life is a topic I return to again and again. I am especially attracted to women from more rural, indigenous cultures. What about the Lowell Mill workers? Women throughout the world have played important roles in virtually every form of constructive peaceable work from antiquity to the present. The piece’s subtitle, Women in Labor, is a play on the concept of women forever giving birth creatively to the world on many levels.

What about the Lowell Mill workers? Women throughout the world have played important roles in virtually every form of constructive peaceable work from antiquity to the present. The piece’s subtitle, Women in Labor, is a play on the concept of women forever giving birth creatively to the world on many levels.

Rather than focusing on a single protagonist, I Want to Go to Jail follows a group of women suffragists and their struggle for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. The drama generally follows

Rather than focusing on a single protagonist, I Want to Go to Jail follows a group of women suffragists and their struggle for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. The drama generally follows

Inside the Charles Street Jail, the suffragists, who have vowed to go on a hunger strike, have been separated and housed in cold cells with buckets for toilets. Suffragist, Betty Gram, who has been jailed before, starts to experience what we would now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (or Acute Traumatic Stress since she is again in jail), as she recalls rats dragging food from her cell during her previous time in jail as an advocate for women’s rights. From their own cells, other suffragists call out their sympathy and support. Others muse about how the world and their homes households are proceeding without them. Eventually, they access their strength and commitment to sisterhood by singing together.

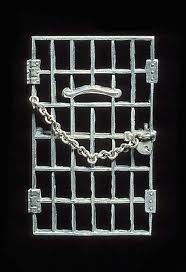

Inside the Charles Street Jail, the suffragists, who have vowed to go on a hunger strike, have been separated and housed in cold cells with buckets for toilets. Suffragist, Betty Gram, who has been jailed before, starts to experience what we would now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (or Acute Traumatic Stress since she is again in jail), as she recalls rats dragging food from her cell during her previous time in jail as an advocate for women’s rights. From their own cells, other suffragists call out their sympathy and support. Others muse about how the world and their homes households are proceeding without them. Eventually, they access their strength and commitment to sisterhood by singing together. In the last scene, the women hold a ceremony at a local theater to honor those who went to jail for the cause and present them with “jailhouse door pins.” It is a momentary pause and time for celebration, for the play appropriately ends with Alice Paul announcing that there is more work to be done, and a new cycle of activism must begin.

In the last scene, the women hold a ceremony at a local theater to honor those who went to jail for the cause and present them with “jailhouse door pins.” It is a momentary pause and time for celebration, for the play appropriately ends with Alice Paul announcing that there is more work to be done, and a new cycle of activism must begin.

The author then describes Marg’s illusory perfect world from Sylvia’s point of view. Marg is a university professor who teaches in the linguistic department who “possessed the room” and commands “a sort of erotic attention [by] her confidence.” Sylvia, a couple of years older than Marg, feels as if she plays second fiddle to her younger sister. Sylvia has worked at a variety of community non-profits doling out food to the homeless and delivering community newspapers door-to-door. She is, by her own half-joking admission, “still trying to find herself.”

The author then describes Marg’s illusory perfect world from Sylvia’s point of view. Marg is a university professor who teaches in the linguistic department who “possessed the room” and commands “a sort of erotic attention [by] her confidence.” Sylvia, a couple of years older than Marg, feels as if she plays second fiddle to her younger sister. Sylvia has worked at a variety of community non-profits doling out food to the homeless and delivering community newspapers door-to-door. She is, by her own half-joking admission, “still trying to find herself.”

Marg listens to Sylvia describe Hugh’s illness and the difficulty of telling Sylvia’s kids (she now has two) and tears up when Sylvia tells her she already finding feels sad to see High’s empty coat hanging in the hall.

Marg listens to Sylvia describe Hugh’s illness and the difficulty of telling Sylvia’s kids (she now has two) and tears up when Sylvia tells her she already finding feels sad to see High’s empty coat hanging in the hall.

This year we are sorry for the passing of

This year we are sorry for the passing of

Eden has wanted to an actress from the time she was very young and is convinced “that she would live far away in great cities, … be much admired by men and … have everything she wanted.” This vision guides Eden throughout her life and she accepts advice (such as changing her name from Edna to Eden) from anyone whom she believes can move her closer to international fame and adoration. She goes to New York, where she believes she is fated to find someone who will take her to Paris. In New York, Eden is for the first time momentarily free to do what she wants, when she meets Hedger who presents her with the opportunity for a new life perspective .

Eden has wanted to an actress from the time she was very young and is convinced “that she would live far away in great cities, … be much admired by men and … have everything she wanted.” This vision guides Eden throughout her life and she accepts advice (such as changing her name from Edna to Eden) from anyone whom she believes can move her closer to international fame and adoration. She goes to New York, where she believes she is fated to find someone who will take her to Paris. In New York, Eden is for the first time momentarily free to do what she wants, when she meets Hedger who presents her with the opportunity for a new life perspective . In Coming, Aphrodite!, Cather presents her readers with a complex discussion of success. Both characters find the success they seek, and Cather is careful to present a neutral view. But by the close of the story one senses that her sympathies lie with the Heroine’s Journey.

In Coming, Aphrodite!, Cather presents her readers with a complex discussion of success. Both characters find the success they seek, and Cather is careful to present a neutral view. But by the close of the story one senses that her sympathies lie with the Heroine’s Journey.